Blondie Johnson (1933) and Smarty (1934)

Tonight I thought it would be good fun to watch two of Joan Blondell’s films. Blondie Johnson is certainly an interesting and worthwhile pre-Code.

Joan Blondell worked for Warners Bros. and after reading her biography, I realized just how much of a work horse she was in a make-work film factory. From the outside, being a movie star has always appeared glamorous to us but in reality, it was mainly a job to most of those people, with perks and a high salary of course.

In 1933 Joan made seven films including Gold Diggers of 1933, Footlight Parade and the controversial and, so far lost film, Convention City.

There are three very interesting aspects in particular to this film. First, it shows us how difficult the Depression was for regular folk, with Blondie going to the government’s Welfare Relief Association asking for help, receiving none. She looks around the room and sees a most sad and bedraggled group of people and realizes that there are even worse case scenarios than hers. There are also other dilemmas she has had to deal with; does she keep a job even though she’s being molested? How does she care for her deathly ill mother? What about her neighbours who are helping them out but are almost as bad off as herself? Later in the film, she talks about how she had a younger sister who “got in trouble” and died. It seems obvious that we’re suppose to construe this information to mean that her teenage sister got pregnant and had an illegal, badly done abortion and died from the results. Although Under Eighteen (1931) also showed what living in the Depression was like, I think this film in particular shows a forceful historical snapshot of how hard times were.

The second aspect is that Blondie chooses to use her brains instead of her body to acquire ill begotten wealth. Considering she sometimes looks like what you would imagine a grown up Shirley Temple would have looked like at the time, it’s quite a feat. She becomes the boss of a gangland syndicate, something that I don’t recall seeing a woman do in any other movie. She has to decide, as well, whether it’s love or business that comes first. Things become rather strange and tense when she has to decide.

The third aspect that’s quite unusual is that there’s an interracial relationship between Lulu (Toshia Mori) and Joe (Donald Kirke) and no one blinks an eye. It’s noticeably refreshing.

There’s great Art Deco furniture and design and the wardrobe is designed by Orry-Kelly, so lots of great style to keep your eyes fixated on. The ending will be worth discussing–was it a perfect pre-Code finish to the story? Would it have appeased both the censors as well as the movie audiences who weren’t offended by risqué stories? Enjoy the film. Caren

April 26, 2014

Blondie Johnson (1933)

Warner Brothers. Directed by Ray Enright and Lucien Hubbard (uncredited). Story by Earl Baldwin Scenario by Alice D.G. Miller. Cinematography by Tony Gaudio. Art Direction by Esdras Hartley. Film editing by George Marks. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Released: February 25, 1933. 67 minutes.

Joan Blondell………………………………………………………………. Blondie

Chester Morris………………………………………………………………. Danny

Allen Jenkins…………………………………………………………………. Louis

Earle Foxe…………………………………………………………………. Scannel

Claire Dodd…………………………………………………………………. Gladys

Mae Busch…………………………………………………………………….. Mae

Joseph Cawthorn………………………………………………………… Manager

Olin Howland…………………………………………………………………. Eddie

Sterling Holloway……………………………………………………………… Red

Toshia Mori…………………………………………………………………….. Lulu

Arthur Vinton………………………………………………………… Max Wagner

Donald Kirke……………………………………………………………………. Joe

Joan finally had her chance at a solo turn with Blondie Johnson. This was her movie outright; she worked every day of its four week schedule. Conceived as a female Little Caesar, Blondie undergoes an extreme transformation at the hands of an indifferent society. As a Depression victim, she appears before a magistrate begging for assistance so that she may care for her sick mother. She gets no sympathy, then goes home to find her mother dead. She hardens quickly. “This city’s going to pay me a living, a good living, and it’s going to get back from me just as little as I have to give,” she says with bitter certainty.

Blondie Johnson gently twisted movie storytelling and sexual stereotypes. This time Joan was not a gangster’s female sidekick, she was the gangster. She became that way by the malfunctions of government, not because of a predisposition to be bad as was often the case in roles played by Cagney and Robinson. There is humor and authenticity in Blondie Johnson, and Joan enjoyed a personal success. She showed a new command on screen, occupying the space with full, confident strides and persuasively shifting from charity case to tough Mafiosa to vulnerable woman in love. It was a tidy hit at the box-office, grossing $325,000, more than twice its negative costs.

Joan Blondell: A Life Between Takes by Matthew Kennedy (2007)

Blondell was one of the workhorses of Warner Brothers in the pre-Code years. Between 1931 and 1933, she made twenty-seven pictures–as many as Garbo made in her entire career. Yet, for all that overwork, Blondell hardly ever had a false moment. Self-possessed, unimpressed, completely natural, always sane, without attitude or pretence, Blondell was the same at twenty-two as she would be at seventy, in Grease (1978): the greatest of the screen’s great broads. No one was better at playing someone both fun-loving yet grounded, ready for a good time, yet substantial, too.

Her best pre-Code role would come in 1933, with Blondie Johnson, as a gangland crime boss. At the start, she is just a girl struggling to find work, so she can care for her sick mother. She can’t get a job, can’t get government assistance, and one day she comes home and finds her mother dead. The truth of Blondell’s reaction, her wild grief and sense of betrayal, underlies and gives dimension to the melodrama that follows.

Complicated Women by Mick LaSalle (2000)

The inevitable distaff version of the gangster film was Blondie Johnson (1933), featuring Joan Blondell in the Rico Bandello (Little Caesar) role. Almost always, good girls gone bad have been forced to sin by extreme circumstances. Whereas Little Caesar is congenitally bad, period, women go wrong for a reason, usually one in trousers, or in Blondie’s case, judicial robes.

When the spunky but penniless Blondie appears before a magistrate, pleading for help on behalf of her sick mother, she seems a nice enough girl. Blondie has tried to find work, but the scarcity of jobs and the paws of brute men foreclose her options. Unmoved, the stern government official brushes aside her pleas. When Blondie returns home, her mother has died of pneumonia. The same fate, she resolves, will not befall her.

Unlike the scheming minx of the bad girl cycle, Blondie relies on her smarts not her body, trading on her looks but not offering sexual favors. She cons men to get ahead, but finally she is a self-made not man-made woman. “I got plans–big plans,” she tells a would-be suitor. “And the one thing that don’t fit in with them is pants.” Like Rico Bandello and Tony Camonte (Scarface), Blondie Johnson is a criminal visionary with the grit to grab for her dream. Like Rico and Tony too, she is brought down by a romantic fixation. The man she loves has married another and perhaps betrayed her to the police. She assents to his murder, but reconsiders and runs to his rescue. Despite the mayhem and murder each has caused, they are sentenced to a token term of imprisonment of six years. As a woman, Blondie can be redeemed and domesticated by true love. A man would have been gunned down in the last reel.

Unlike the scheming minx of the bad girl cycle, Blondie relies on her smarts not her body, trading on her looks but not offering sexual favors. She cons men to get ahead, but finally she is a self-made not man-made woman. “I got plans–big plans,” she tells a would-be suitor. “And the one thing that don’t fit in with them is pants.” Like Rico Bandello and Tony Camonte (Scarface), Blondie Johnson is a criminal visionary with the grit to grab for her dream. Like Rico and Tony too, she is brought down by a romantic fixation. The man she loves has married another and perhaps betrayed her to the police. She assents to his murder, but reconsiders and runs to his rescue. Despite the mayhem and murder each has caused, they are sentenced to a token term of imprisonment of six years. As a woman, Blondie can be redeemed and domesticated by true love. A man would have been gunned down in the last reel.

Pre-code Hollywood: Sex, immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930-1934 by Thomas Patrick Doherty (1999)

The 1933 film Blondie Johnson typified the efforts of the inventors of the gangster to explore the new territory on which modern men and women interacted and to fashion values that would guide others over that terrain. In an unusual plot variation, the eponymous heroine is a gang leader and thus a personification of women’s potential independence. Trouser-clad Blondie, suggesting modern society’s blurring of conventional gender categories, is sarcastic, strong, and defiant, and she professes to care about nothing except her own material advancement. The film centers on the problematic dynamics of power between men and women. Warner Brothers publicity boilerplate played up that enticing angle:

In her long list of screen successes Joan Blondell has invariably been ruled by men. She’s been slapped and cheated–often she’s been the sacrificing girl who lets “her man” go to another–but throughout the string of pictures in which she has appeared, a man has dominated her. Now along comes Blondie Johnson….As Blondie Johnson Joan not only refuses to allow the male to govern her, but she rules that species with a hand of iron.

Blondie is an exciting, sympathetic embodiment of women’s power. Nevertheless, at film’s end, she reforms and recognizes not only the error of her criminal ways but, more important, the error of ignoring her female nature. Finally admitting her love for the man who has pursued her, she promises to be faithful. When he tells her, “you’re a fresh dame,” Blondie corrects him: “Sweetheart to you, Danny.” The modern woman, the underworld again taught, could be and must be domesticated.

Investing the Public Enemy: The Gangster in American Culture, 1918-1934 by David E. Ruth (1996)

ENTERTAINING RACKETEER DRAMA WITH FEMININE MASTER MIND. GOOD PRODUCTION OF ITS KIND.

A fresh twist is given here to the gangster melodramas by having a girl as the brains behind the works. Joan Blondell, made bitter against the world when her mother dies following eviction from their squalid small-town home, comes to the city with the sole idea of getting all she can and giving as little as possible. Meeting a slick young gangster, Chester Morris, who is right-hand to the big shot in control of all the city’s rackets, she encourages and promotes him into dethroning the boss and taking his place. Then when the new dictator goes high-hat, she forces him out and takes charge herself. Eventually the gang is busted up by the police, with Joan and Chester pledging to go straight together after they finish their jail terms. Miss Blondell does some of her best work and shows dramatic ability in some of the scenes.

The Film Daily, March 1, 1933

WHAT SHOCKED THE CENSORES!

REEL 2 – Eliminate: “Six different guys to the tune of forty bucks; that’s twenty apiece.”

“All we want is to get a line on the judge.”

“Juries are simpler.”

“Then you can give me your idea about the jury, see.”

“….and that sacred message rests under the heart of that little woman.”

…”The cruel mockery that we’ve perpetrating here makes me cast aside respect for statutes, to shout condemnation at man-made laws.”

“Should have had the Swede on the jury.”

“Those once big, shiny eyes of hers look now through tears toward woman’s greatest glory–motherhood.”

REEL 4 – “Working on his own–my racket–with that blond bag.”

“There’s no limit to this new field we’re going to get in. Here’s your cut.”

Eliminate all view of Blondie distributing money, received from shakedown, to her confederates, Mae and Lulu.

REEL 5 – Eliminate all view of machine gun shown in opening in back of trick bar.

Eliminate view of Max’s hand covered with blood.

REEL 6 – Eliminate italicised words: “And as long as you and the boys are getting your cut, I don’t see why you worry about what I do.”

A complete record of cuts in motion picture films ordered by the New York State Censors from January, 1932 to March, 1933

Published by THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON FREEDOM FROM CENSORSHIP

(Organized by the American Civil Liberties Union)

“BLONDIE JOHNSON,” FAILS TO STARTLE; RATED AS FAIR ENTERTAINMENT

Blondie Johnson, which should, and perhaps could, have been one of the big (and when we say big, we mean BIG) Warner Bros. productions of the year, turned out to be only fair entertainment.

Its story, which deals with a woman racketeer who achieves big things in her line and who eventually is forced to have her racketeer lover put on the spot to satisfy the whims of her mob, is film matter which should carry a punch. It somehow falls short of its expectations. It is only the fine acting of Joan Blondell and Chester Morris that saves the picture from being an altogether total flop.

Joan Blondell’s emotional scenes in the opening shots of the picture are, in this writer’s estimation, about the finest bits of acting she has ever performed on the screen. The rest of her sequences are devoted to idle chatter and many would-be smart cracks.

Ray Enright’s direction smacks of throughness while the photography of Tony Gaudio is both novel in its effects and intelligent for the picture runs along smoothly. Earl Baldwin supplied the screen play.

Ray Enright’s direction smacks of throughness while the photography of Tony Gaudio is both novel in its effects and intelligent for the picture runs along smoothly. Earl Baldwin supplied the screen play.

Hollywood Filmograph by Hal Wiener, January-December 1933

Having played second fiddle to some of the screen’s most eminent public enemies, Joan Blondell branches out for herself in “Blondie Johnson,” which is at the Strand. Cast into the street by a heartless landlord, Blondie is first revealed as a resentful young woman who has arrived at the conclusion that virtue does not pay. Lacking a definite program for her iniquitous ambitions, she begins in a small way by playing on the sympathies of sentimental young men for money to convey her to a hypothetical dying mother. Thereafter in a racy melodramatic style the picture describes her gradual rise in the underworld, her manner of eliminating troublesome competitors and the ingenious machinery she sets in motion for extorting money from fashionable jewelers.

As a gangster melodrama this one is effective. The dialogue abounds with the picturesque argot of the underworld. The story reveals frequently a lively sense of humor and the actors cooperate with good performances. Of course, the film’s best asset is Miss Blondell herself, who is ingratiating, cynical and tartly amusing. Allen Jenkins portrays a droll scofflaw, and Chester Morris is tight-lipped and ruthless as Blondie’s consort.

The particular “insurance” racket out of which Blondie and her henchmen make their fortunes is a model of its kind, retaining a shrewd balance on the fence between good and evil. Eventually Mr. Morris, as the “front” for the outfit, makes the mistake of trying to seize all the power for himself. The internal warfare that follows brings the police in with a whoop, and the whole gang receive prison sentences which it is presumed will not be so extensive as to make Blondie and her chief lieutenant lose sight of their affection for each other. Ray Enright, the director, has developed the story with speed and clarity.

The New York Times by A.D.S., February 27, 1933

Joan Blondell is playing “Blondie Johnson.” When you see her in the picture, you will find her wearing some very smart clothes. One of them is this evening ensemble. The short jacket is beige with brow buttons. The sleeves are fitted to the elbow where fullness starts. Note the wide lapels. The dress of brown crepe is designed for double duty purposes, it may be worn evenings without the jacket.–Photoplay January 1 to June 30, 1933

BLOGGERS’ CURRENT REVIEWS

http://selfstyledsiren.blogspot.ca/search?q=blondie+johnson by The Siren, June 12, 2012

http://pre-code.com/blondie-johnson-1933-review/ by Danny, January 4, 2013

http://nitratediva.wordpress.com/2013/02/09/blondie-johnson/ by The Nitrate Diva, February 9, 2013

http://dfordoom-movieramblings.blogspot.ca/2013/02/blondie-johnson-1933.html by dfordoom, February 14, 2013

http://immortalephemera.com/43241/blondie-johnson-1933/ by Cliff Aliperti, September 29, 2013

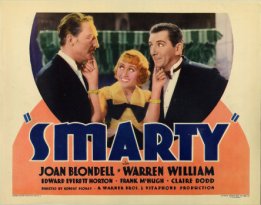

Smarty (1934)

Smarty is one of those films that would be considered a precursor to the “Screwball Comedy”. It’s a cute film with all the topics we love in a pre-Code, ranging from wife slapping, impotence, infidelity and female brattiness.

In 1934, Joan made five films including Dames, two less than in 1933. This would have been due to the fact that she was pregnant with her son Norman. She was married to cinematographer George Barnes, who was also the cameraman for this film. I’m sure that’s why Joan looked especially lovely.

There’s a fabulous dress in this film that’s hard to keep your eyes off, mainly because you’re so impressed that nothing untoward happens, if you get my drift. Just in case you’re not sure, it’s the one with the bow.

So again, I hope you enjoy this film. Caren

Warner Brothers. Directed by Robert Florey. Based on the play by F. Hugh Herbert, screen play by F. Hugh Herbert and Carl Erickson. Cinematography by George Barnes. Art Direction by John Hughes. Film editing by Jack Killifer and Howard Bretherton (uncredited). Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Released: May 19, 1934. 65 minutes.

Joan Blondell………………………………………………………………….. Vicki

Warren William……………………………………………………………….. Tony

Edward Everett Horton…………………………………………………… Vernon

Frank McHugh……………………………………………………………. George

Claire Dodd………………………………………………………………….. Anita

Joan Wheeler…………………………………………….. Mrs. Bonnie Durham

VirginiaSale…………………………………………………. Edna, Vicki’s Maid

Leonard Carey……………………………………………. Tilford, Tony’s Butler

Warner Bros. shoved Joan into Smarty, an odious programmer shot in eighteen days. Smarty came out just prior to the PCA’s crackdown on sins of the flesh, so it could still mention “diced carrots” as veiled code for impotence.” More tawdry was the comedy and romance made from homespun violence–Hit Me Again was the project’s working title.

Joan Blondell: A Life Between Takes by Matthew Kennedy (2007)

Love even hurt Warren William. The late pre-Code Smarty (1934), one of the most peculiar items in the William filmography, teamed him with Joan Blondell, but an unusually flighty Blondell, in a role originally intended for Genevieve Tobin. Blondell and William are married, and one night, over dinner, with friends present, she needles him mercilessly. “You make me absolutely impotent with rage,” he grumbles. To which she replies, “You mean diced carrots?” Whereupon, he leaps up and smacks her before he even knows what he’s done.

Diced carrots? The reference returns later in the movie, when the wife tells a friend that diced carrots refers to “a little intimate married secret” between her and her husband–an incident of impotence, most likely, since the phrase “impotent with rage” brought about her mentioning it. Jokes about impotence, albeit silly veiled ones, are not something one expects in a 1934 movie.

Dangerous Men by Mick LaSalle (2002)

As Warren William, a divorce lawyer, says to a man in Smarty (1934): “In marriage, when you leave before the final curtain, you get no privileges.” Originally titled Hit Me Again, Smarty was a dubious marriage comedy about spousal abuse. The pressbook suggested theater owners should sponsor newspaper contests in which local moviegoers could write up their own experiences of abuse–“but make ’em funny.”

I Do and I Don’t: A History of Marriage in the Movies by Jeanine Basinger (2012)

RAMBLING TALE OF MARRIED LIFE AND DIVORCE FAILS TO DEVELOP FARCE POSSIBILITIES.

A distinctly farce idea, the business and dialogue were written away from the comedy elements, and the director evidently was misled also, into thinking he had a more or less serious work on his hands. The results is that the actors are anything but at their ease in trying to read a serious note into situations that should have been farcical and funny. The story rambles in and out of situations that are not any too closely knit together, and the result is a very neutral offering. Joan Blondell has the role of a very willful and exasperating wife of Warren William. She is having a little romance with Edward Everett Horton, a lawyer. At a bridge party hubby slaps his wife’s face when she provokes him unbearably. Then the divorce, and the lawyer friend marries her. Then business of turning the tables with an almost identical situation. The fickle girl then plays for her ex-hubby, and the climax leaves you believing she will get him back. Miss Blondell is forced to play the part of a very disagreeable girl that won’t add to her popularity.

The Film Daily, April 12, 1934

The trouble with this is a director who doesn’t know how to be lightly funny and actors who try too hard to be. Edward Everett Horton as a sympathetic attorney emerges from the ordeal with his reputation undamaged. That is more than can be said for Warren William as a supposedly comic husband, who isn’t, and Joan Blondell who tries to play a fascinating wife so vigorously that she makes the lady a moron.

This is another of the matrimonial triangle situations–jealous husband, flighty wife, ardent bachelor–and parts of it are laughable but the determined high pressure under which everyone has worked makes the film more of a cartoon than a comedy. Frank McHugh and Claire Dodd also appear. They aren’t much help.

by Frederic F. Van de Water, The New Movie Magazine, July 1934

THE FILM ESTIMATES

Being the Combined Judgments of a National Committee on Current Theatrical Films

Estimates are given for 3 groups

A–Intelligent Adult

Y–Youth (15-20 years)

C–Child (under 15 years)

Bold face means “recommended”

Sophisticated, rambling, farcical, domestic comedy with fast tempo but lacking in spontaneity and humor. Heroine is an unpleasant person who likes cavemen and rushes from one husband to another alternately, with expected complications. Waste of cast.

A–Absurd Y–No C–No

The Educational Screen, September 1934

A sophisticated comedy in which Joan Blondell and Edward Everett Horton do nice work. Supporting them are Warren William, Frank McHugh, Claire Dodd, Joan Wheeler, Virginia Sale and Leonard Carey. Robert Florey directed with a whimsical touch.

As a spiteful and spoiled wife, Miss Blondell irks her husband to the point where he forgets himself and slaps her in front of guests in their home. The incident leads to divorce, which the kittenish wife has desired all along. This gives her a chance to marry Horton. At the same time it makes her ex-husband, William, feel foolish, for later he is invited to the home of his divorced wife and gets a chance to review the happenings of which he already has been a victim.

Later, Miss Blondell leaves her husband, and goes to William’s apartment. There she finds he is entertaining another woman. Her husband follows her to the William apartment and finds her in a bathrobe. A scene follows and when it is all over William and Miss Blondell are left alone and decide to get married all over again. However, the husband promises not be the meek and coddling kind.

McHugh provides comedy moments.

Motion Picture Daily, May 9, 1934

BLOGGERS’ CURRENT REVIEWS

http://screensnapshots.blogspot.ca/2010/11/smarty-1934-joan-blondell-shows-funny.html by Russell on November 13, 2010

http://letsmisbehaveprecodefilmtribute.blogspot.ca/2012/08/not-for-faint-hearted-smarty-1934.html by Emma, August 13, 2012

http://pre-code.com//?s=smarty by Danny, May 17, 2013

Joining me for the evening was Ronda, Christiane, Scott, Allen, Karen, Hanna, Arny, Lee, David, Betsy, Peggy, Andrea and Rolf.